Not only had 13 years passed since Larry Zeidel had last played in the NHL, so had six new teams on him in an expansion draft until he sent a professionally-produced brochure marketing himself.

“I can help your organization in the front office with my experience in ticket sales and public relations as well as on the ice,” began a presentation in which Zeidel was pictured in both a hockey uniform and a business suit.

“In case someone wanted me as a coach or manager I had to look dignified,” he recalled years later in Full Spectrum, the Complete History of the Philadelphia Flyers. The new Flyers had filled those primo jobs with Bud Poile and Keith Allen. But having both coached Zeidel in his long road through the minors they knew there wasn’t a player taken in the great 1967 expansion who wanted more badly to be in the NHL.

So two weeks into season one, they offered the 39-year-old Zeidel better just than a ticket-selling job, even though they probably thought the presence of a Jewish player – still the only known one in franchise history – might fill some of the rows of empty seats at the Spectrum.

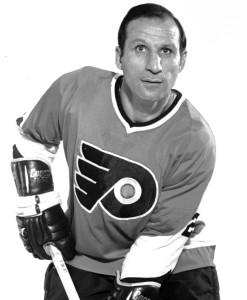

At the time of his death Wednesday, Zeidel had been the oldest living Flyer. Photo credit – PhiladelphiaFlyers.com

“All I have to do is see this carpeting in the locker room and I’m motivated,” said Larry (The Rock) Zeidel, who was the oldest living Flyer until he died Tuesday at 86. “We never had carpeting in the minors.”

As the Flyers took the lead in the new West Division, where all the new teams had been placed, Zeidel earned his keep through Year One in an effective defense partnership with a 24-year-old Joe Watson.

“He was tough, demanded respect out there,” recalled Watson yesterday. “Even at practice.

“He thought Brit Selby needed toughening up, so one time at practice ‘The Rock’ went after him.”

Zeidel was a hockey nomad who probably had as much as anyone to do with rooting that first Flyer team to Philadelphia. In becoming the franchise’s first real character, he helped gave it a spine.

After the Flyers were orphaned by an early March storm that damaged the Spectrum roof, the second home game that had to be moved was in Toronto, one day after the team, 1-8-2 in their last 11 games, had been ripped 7-2 there by the Maple Leafs.

“I looked at the mood, I see the team is down,” Zeidel recalled. “I figure I’m going to turn it up to high.

“I didn’t need an excuse, I’d had a thing going with the (the Bruins) Eddie Shack for a long time. The last time we were in Boston, the two of us had bumped during the warmup. I figured it was time to balance the books. So I went to the game like a kamikaze.”

In the opening minutes, Shack and Zeidel collided and traded insults. Later in the first period, they again came together along the boards and Zeidel swung his stick and opened a three-stitch cut on Shack’s head. Enraged, the Bruin began flailing away, swinging seven times at Zeidel, who held his stick horizontally in front of his face to escape with only a three-stitch cut on his scalp.

“It started at center ice and ended behind the goal,” recalls Watson. “By the end, they were down to twigs.”

And still The Rock didn’t think it was over. While getting stitched, he learned that Shack was being treated in an adjacent room. “He took off, the needles still in his head and all,” recalls Watson. “Doctors chasing him, cops restraining him.”

The wire service pictures of two bloodied players swinging at each other horrified two nations and even shook up hockey people. “It was one of the worst stick fights I’ve ever seen,” said NHL officials supervisor Frank Udvari.

After the game Zeidel said the incident had been prompted by anti-Semitic remarks made by the Bruins, then later admitted he had made that part up. But there was method to the madness. Although a Flyers third-period rally had fallen short, Zeidel seemed to have galvanized them. As Quebec City became their home away from home for the rest of the season, they won the division regardless before the Blues beat the Flyers in Game Seven at the re-opened Spectrum.

Over the summer the Flyers added 40-year-old future Hall of Famer Allan Stanley and released Zeidel, the 40-year-old gritty journeyman nine games into the next season. After hockey, he worked as a marketing consultant for an investment house and was a regular at Flyers home games. His marriage having ended 30 years ago, in his final years Zeidel lived with Joan and George Bradley in their Mayfair home.

Visitation and services will be held Saturday, 8 a.m. to noon, at Cassizzi Funeral Home, 2915 East Thompson St., Philadelphia, the Flyers and their alumni association sharing the cost of a proper goodbye for a Flyer who helped cause a city with little hockey heritage to say hello to the sport.

“He helped define Philadelphia Flyers hockey,” said Ed Snider. “He was a tough son of a gun on the ice and a terrific fighter, a colorful guy and he was that way his whole life.”

Philly Sports Jabronis

Philly Sports Jabronis